Iran Election 2021: Emerging Electoral Boycott In Iran Reflects Growth In Support For MEK

Written by

Mohammad Sadat Khansari

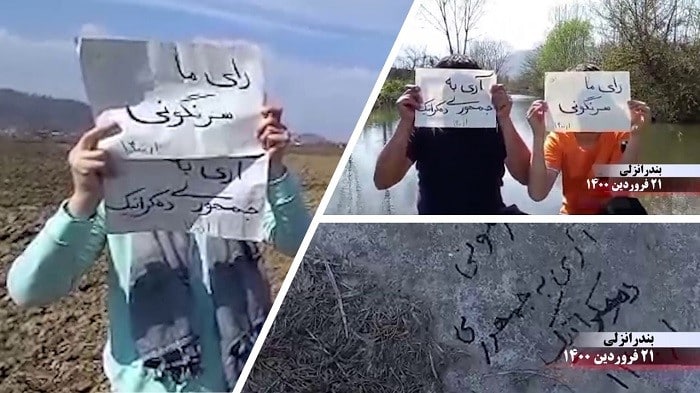

Bandar Anzali – Activities of the Resistance Units and supporters of the MEK, calling for the boycott of the regime’s sham election – April 10, 2021

Iran’s leading voice for a democratic future, the People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran (PMOI/MEK), has long encouraged the Iranian people to avoid participation in the current regime’s elections on the understanding that the process is a sham.

The country’s theocratic system of government ostensibly allows for the popular election of a president and members of parliament, but it also invests a tremendous amount of power into unelected officials and institutions like the regime’s Supreme Leader and the Guardian Council. The latter is specifically tasked with vetting all political candidates and all new legislation according to criteria that include loyalty to the Supreme Leader himself. Consequently, only candidates with absolute loyalty to the supreme leader are allowed to hold high office.

As the MEK makes clear with every election cycle, the “reformist” faction of Iran’s current political system is badly misnamed. In all the most important matters, its members are of one mind with their “hardline” colleagues. Elections are, therefore, little more than a scheme for sharing power among two elite interest groups. Victory for one faction or the other has never translated into a meaningful curtailment of the social or economic crises facing the Iranian people. Indeed, these problems have rather steadily escalated for more than four decades since the creation of the Iranian regime.

This trend certainly remained recognizable throughout the past eight years, when Iran’s government was nominally headed by the so-called reformist President Hassan Rouhani. Upon his first-term election in 2013, some of Rouhani’s Western counterparts embraced his surprise electoral victory and even went so far as to suggest that Iran’s pro-democracy youth had been in some sense vindicated for their participation in the 2009 protests, which questioned the reelection of Rouhani’s “hardline” predecessor, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

Inside of Iran, however, enthusiasm for Rouhani was far more muted. Within months of taking office, regarding almost all the issues, he and his advisers were publicly insisting that the president had no influence over the decisions or conduct of an “independent” judiciary, regardless of its well-established focus on suppressing dissent and enforcing fear of government authority.

The administration’s statements on topics reflected a clear, deliberate abdication of responsibility, and they were repeated again and again in the context of other issues that had been the source of widespread discussion and protest within the Iranian activist community. As a consequence, people’s hatred towards Rouhani is not to say that it brought support over to his nearest challenger, an ultra-hardline judge named Ebrahim Raisi, whose central claim to fame is a major role in the 1988 massacre of political prisoners, which primarily targeted the MEK and over 30,000 political prisoners were massacred.

Instead, the 2017 presidential election saw a sharp increase in the number of Iranians boycotting the polls altogether and demonstrating that they saw no path forward for Iran under the leadership of either political faction. Both of those factions did whatever they could to cover up the upward trajectory of the MEK’s boycott campaign. State media during that election cycle broadcast images of long lines a polling places, but citizen journalists provided evidence that these images often depicted members of the regime’s civilian militia, the Basij, who traveled from location to location, padding out the numbers and compelling bystanders to participate in a process that many of them saw little value in.

The purpose of this propaganda was, of course, to present the image of popular recognition of the regime’s legitimacy. But the same propaganda also served to conceal the extent to which the Iranian people, increasingly outraged at their own government, were naturally gravitating toward the nearest viable alternative: the MEK and its parent coalition, the National Council of Resistance of Iran.

While the 2017 electoral boycott hinted at the popular embrace of the MEK, this phenomenon was made unmistakable at the very beginning of 2018, when protests erupted in more than 100 cities and towns, all featuring anti-government slogans and calls for regime change which had been popularized by MEK “Resistance Units.” The MEK’s role in planning and facilitating the protests was acknowledged by no less an authority than the regime’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, who delivered a speech at the height of the uprising in which he stated that the MEK had “planned for months” to capitalize on public discontent over the entire government’s mismanagement of economic and social affairs.

The 2018 uprising was eventually brought under control following the deaths of dozens of peaceful protesters. But it also led to what NCRI’s President-elect, Mrs. Maryam Rajavi, called a “year full of uprisings.” This, in turn, set the stage for another, even larger uprising in November 2019. In that case, nearly 200 localities became hosts to the same anti-government slogans, and the regime, in its panic, directed authorities to open fire on crowds of protesters, killing 1,500 in a matter of days.

It could be argued that those killings were the final nail in the coffin for the narrative of a reformist political faction that is materially different from its hardline “alternative.” Taking place under Rouhani’s watch, the November 2019 crackdown was the worst single incidence of repression in decades, and no major reformist figure took action to stop it or even stepped up to criticize it after the fact.

Iran, IRGC, Iran Protests, MEK, NCRI, uprising

The November 2019 nationwide uprising in Iran

It should have come as no surprise, then, that when parliamentary elections took place just three months later, they received the lowest voter turnout in the history of the regime. Tehran attempted to explain this away as a reaction to the coronavirus pandemic, but the regime had deliberately avoided acknowledging local infections in order to encourage the highest level of participation possible.

The failure of that scheme suggests that the mullahs will struggle from this point forward to create an image of their own legitimacy from the thin veneer of Iranian democracy. At the same time, there is no sign that public support for the MEK will do anything other than continue to trend upward, reaffirming the support for its platform that was put on such prominent display in January 2018 and November 2019.

Next month’s sham presidential elections may be the latest proving ground for this trend. The MEK Resistance Units are presently operating in cities throughout the country with the goal of promoting an electoral boycott. Graffiti, posters, and placards in each of those localities tend to frame this activity specifically as “voting for regime change.” And this is a message that has not gone unnoticed by Iranian officials and Iranian state media.

Many of them have warned that low voter participation could be a precursor to more social unrest on the scale of the recent uprisings. In recent speeches, Mrs. Rajavi has pointed out that the signs of that unrest are already visible in the form of protests by marginalized fuel porters, struggling pensioners, swindled investors, and others. In each of these cases, participants in the protests have been heard to plainly endorse the electoral boycott with slogans like “we have seen no justice; we will not vote.”

In this way, they are demonstrating the unity of purpose among all of their causes – a unity that evidently is facilitated in large part by the MEK.