Iran Policy Should Prioritize Human Rights Before Ominous Presidential Transition

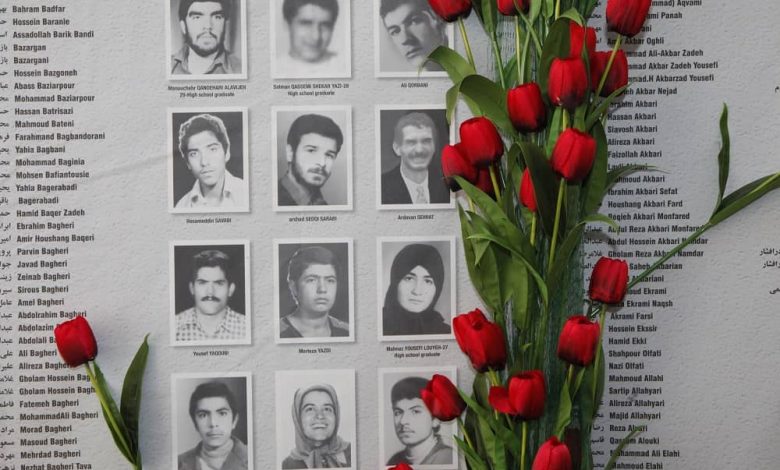

Victims of 1988 Massacre in Iran

Written by

Mansoureh Galestan

In the summer of 1988, “death commissions” throughout Iran systematically interrogated, condemned, and executed 30,000 political prisoners as part of an effort to stamp out organized opposition to the fledgling theocratic dictatorship. In the more than three decades since, no one has been held accountable for the killings. Quite to the contrary, officials who participated in the massacre have repeatedly been rewarded for their commitment to violent repression.

Many of those rewards have come in the form of appointments to government positions that are deeply ironic insofar as they ostensibly serve to promote justice. Both the current and the former Ministers of Justice for the entire regime were previously members of the death commissions in 1988. Both the outgoing and the newly appointed head of the national judiciary also played substantial roles in the massacre, one as a member of the Tehran death commission and the other as the judiciary’s representative to the Ministry of Intelligence and Security.

The former, Ebrahim Raisi, was confirmed as the new president of the Iranian regime on June 18, after a tightly controlled electoral process in which the vast majority of the Iranian population refused to participate. According to the National Council of Resistance of Iran, many polling places remained empty that entire day and lent support to the conclusion that the voter participation rate was less than 10 percent.

The electoral boycott is a profound statement denying legitimacy to the new president and to the entire system underlying his “election.” Indeed, the NCRI’s main constituent group, the People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran (PMOI/MEK), promoted the boycott to the domestic population as a means to “vote for regime change.” The MEK Resistance Units conveyed that message via graffiti, posters, and illegal public demonstrations in hundreds of towns, for months prior to the election. A number of those activists highlighted their efforts for an international audience as well, via anonymous messages to the Free Iran World Summit.

Highlights: Free Iran World Summit 2021-The Democratic Alternative on the March to Victory- July 10

That event took place between last Saturday and Monday, and also featured the participation of NCRI officials and dozens of Western political dignitaries. Hundreds of thousands of Iranian expatriates watched a live stream of the summit, many of them from simultaneous gatherings in 17 world capitals. Mrs. Maryam Rajavi, the NCRI’s President-elect delivered a keynote address on each of the event’s three days. Her final speech, in particular, emphasized the regime’s abysmal human rights record, the likelihood of further deterioration under Raisi’s leadership, and the role that the international community might play in diminishing or preventing that effect.

“As far as the international community is concerned,” Mrs. Rajavi said, “this is the litmus test of whether it will engage and deal with this genocidal regime or stand with the Iranian people.” She went on to say that Raisi is “guilty of genocide and crimes against humanity,” having compounded the legacy of his participation in the 1988 massacre by repeatedly justifying and defending it, and applying the same repressive principles to his more recent roles within the regime.

As judiciary chief, Raisi was one of the main figures overseeing what may have been the worst crackdown on dissent since the time of the massacre. In November 2019, Iran was rocked by a sudden outpouring of anti-government protests in nearly 200 cities and towns. Having already faced a similar, if slightly smaller uprising in January 2018, regime authorities responded with panic, opening fire on crowds all across the country. Approximately 1,500 people were killed in a matter of days, and at least 12,000 were arrested. For months afterward, the judiciary subjected many of those arrestees to systematic torture, aimed both at punishing them for their dissent and at securing false confessions that might later justify prosecution and harsh sentencing, including the death penalty.

Based on all of this, Mrs. Rajavi said, the international community should strive to isolate Raisi and ultimately make him the focus of formal inquiries into Iran’s unanswered crimes against humanity. The NCRI leader specifically urged the United Nations to bar Raisi from attending the next meeting of the General Assembly – a recommendation that was echoed by several other participants in the Free Iran World Summit.

Former US Senator Robert Torricelli said, for instance, “If the United Nations decides that Raisi belongs to the United Nations, then the United Nations does not belong in New York. We must not host terrorists, despots, and mass murderers.”

Senator Robert Torricelli’s Remarks to the Free Iran World Summit 2021- July 12, 2021

Of course, the implications of that sentiment extend far beyond the world’s interactions with the Iranian regime’s president-elect. It theoretically fuels a call for actions targeting all leading Iranian officials, and certainly all those who are known or suspected to have participated in the 1988 massacre. Mrs. Rajavi referenced Raisi right alongside the regime’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and the new judiciary chief, Gholamhossein Mohseni Ejei when urging “the UN Security Council to take action to hold the leaders of the mullahs’ regime accountable for committing genocide and crimes against humanity.”

In speaking at the Free Iran World Summit, Slovenian Prime Minister Janez Jansa said the international community has “forgotten” about the 1988 massacre “for almost 33 years.” The entire event aspired to bring that issue back to the forefront of policymakers’ minds, and Raisi’s pending inauguration should do the same. As Mrs. Rajavi said, the advent of the new administration is indeed a litmus test for the international community’s commitment to universal human rights principles and the global triumph of democracy.

In these final weeks, anyone with the means to shape Western policies toward Iran should be exerting all available pressure in favor of making the regime’s human rights record a centerpiece of such policies. When this is done, it should be impossible for the world to again “forget” the legacy of 1988, to ignore Raisi’s role in it, or to welcome him as Iran’s representative on the world stage without being aware of how deeply this insults the entire population that rejected Raisi’s sham election in June.