Mass Infection of Inmates Renews Questions About Abuse and Neglect in Iranian Prisons

Written by

Mansoureh Galestan

Mass Infection of Inmates Renews Questions about Abuse and Neglect in Iranian Prisons

On Saturday, Iranian regime’s President Hassan Rouhani acknowledged that in one Iranian prison, 100 out of 120 inmates became infected with Covid-19 before authorities were even able to recognize that the coronavirus had been introduced to the population.

It was a shocking admission coming from a president – and an entire regime – that has been reflexively dishonest about almost every single aspect of the global pandemic’s impact on his country.

In the days before Rouhani spoke on the prison outbreak, the regime Ministry of Health reported that the number of fatal cases of Covid-19 had surpassed 6,000 in Iran. But this number is widely suspected to be a deliberate undercount, and some sources indicate that the real death toll is several times greater. On Monday, the National Council of Resistance of Iran (NCRI) reported that the number of fatalities had reached 40,700 across 316 cities.

As well as keeping track of the overall impact, the NCRI has been sounding alarms about the dire condition of Iranian prisons, while dispelling the regime’s own efforts at damage control. The Iranian regime’s judiciary has claimed, at various times, to have released as many as 100,000 prisoners on bail as part of an effort to slow down the spread of the disease. But at the same time, authorities have generally denied that outbreaks in prison were a serious problem.

Rouhani’s statement on Saturday directly invalidating this latter claim. It also indirectly cast further doubt on the official narrative about the status of prison populations. If a single vector for the novel coronavirus was able to spread the infection to 100 people before the outbreak was even recognized, it stands to reason that the facility in question remained severely overcrowded at a time when the judiciary claimed to have furloughed upwards of one-third of the entire country’s prison population.

Even before the entire world was in the grip of a pandemic, the overcrowding in Iranian prisons was notably inhumane. Close confines were known to exacerbate the effects of poor sanitation, lack of access to medical treatment, and a range of other harsh conditions stemming sometimes from simple neglect and sometimes from a malicious impulse toward extrajudicial punishment.

Denial of medical services is regularly identified as a tactic used by regime authorities to put pressure on political prisoners and other inmates who are deemed unruly or problematic. Many individuals have died as a result, while others have suffered permanent health effects including organ failure and amputation as a result of untreated cancers and other ailments.

One can easily imagine how prevalent this sort of neglect has become in the midst of coronavirus outbreaks. As more information becomes available about the effects of that disease, it is clear that it does more than just kill the elderly and infirm. Even younger patients have been known to experience strokes and hemorrhaging brought on by Covid-19, and among those who have recovered, many are expected to suffer from permanently reduced lung function.

This is all true even within countries that have competent governments and well-run health systems, as well as prison facilities that generally abide by international human rights standards. None of this applies to Iran. Iranian doctors and nurses have routinely risked arrest to make citizens aware of a situation that is being covered up by the clerical regime, in which hospitals are overwhelmed and hundreds of people are dying across multiple cities on a daily basis. The regime, meanwhile, is sending people back to work while falsely claiming to those certain areas of the country have reduced the spread of illness to negligible levels.

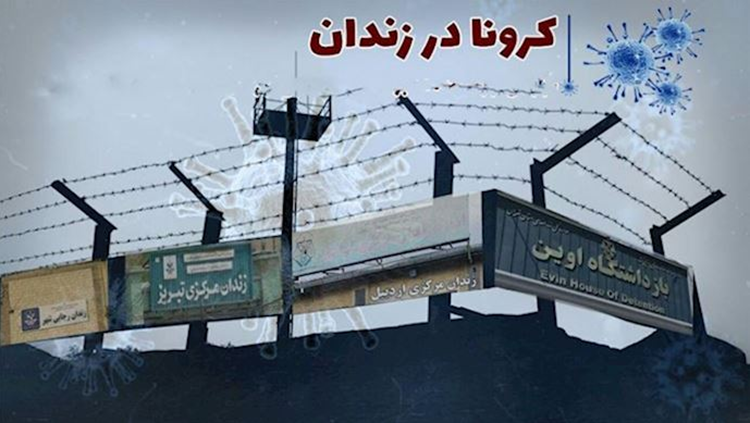

This disregard for its own people comes as little surprise to people who understand the nature and history of the Iranian regime. And those same people understand that its disregard for the general population pales in comparison to its disregard for the prison population. Long before Rouhani’s acknowledgment of a recent outbreak, this led to questions about what had been going on behind the walls of facilities like Evin Prison.

Those places are no strangers to mass death or to the aggressive enforcement of secrecy. That, of course, is a dangerous combination. Although the Iranian regime is well-recognized for having the highest per-capita rate of execution in the world, the actual number of annual hangings is never precisely known, because many of them go unrecorded in official documents. They are only made known to the world through the tireless work of activists, including those still detained alongside death row inmates.

By the regime’s own admission, these political prisoners, or “national security case,” were not included in the furlough arrangements that were first announced in March. But some prisoner-activists were quick to declare that they had seen no sign of the widespread releases that authorities had announced. In an open letter announcing a hunger strike, inmates at Greater Tehran Penitentiary noted that even though some people had disappeared from their cells, few had been given formal notice of transfer or release.

This in turn has fueled speculation about enforced disappearances, which cannot be easily dispelled in absence of independent confirmation of the judiciary’s mass furloughs. As it stands, reports of those furloughs depend entirely on the testimony of the judiciary head, a known human rights abuser who was among the leading perpetrators of a mass execution of prisoners in 1988, which claimed an estimated 30,000 lives.

Increasingly, though, those reports are being contradicted by the details that are shared with the public by civil activists, political prisoners, independent journalist, and occasionally, regime officials. Since furloughs were announced, several prisons have been host to rights and breakout attempts driven by concerns over Covid-19. Amnesty International has confirmed that at least 36 inmates were killed in the regime’s reprisals, to say nothing of those who died of illness, abuse, or neglect in the run-up to the unrest.

All of these underscores the vital need for international human rights monitors to access the Iran and evaluate the condition of its prisons. Tehran has always refused to comply with such requests, and this is unlikely to change in the midst of the pandemic. But the global crisis should not distract human rights advocates from the mission of putting pressure on the Iranian regime over these matters. If that regime is able to get away with lying on such a grand scale about safeguarding the lives of its prisoners, what other deceptions will it be able to get away with in the future?