Iran Mullahs’ Denial of Corruption Falls Flat Amidst Recurring Popular Uprisings

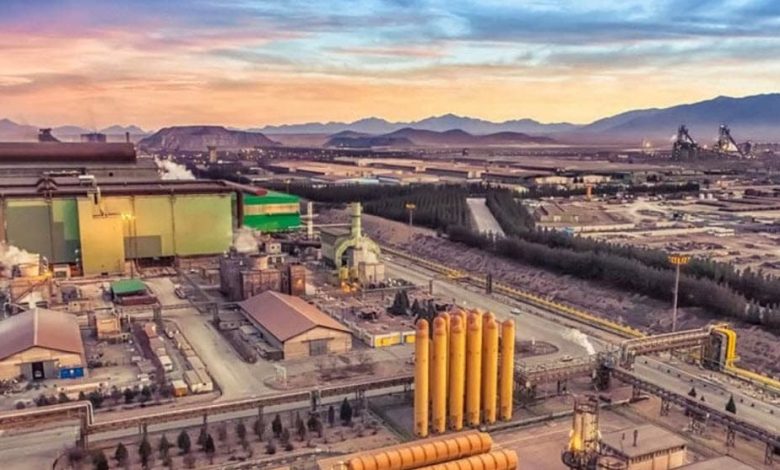

Mobarakeh Steel Company Facilities in Isfahan

Written by

Shamsi Saadati

Last month, the Tehran Stock Exchange suspended trading of shares in Mohbarakeh Steel Company, the second most highly-valued entity on the exchange. The Iranian company is the largest steel plant in the entire Middle East/North Africa region. It is also a source of shameless, staggering financial corruption.

A damning August report by the regime’s parliament revealed that Mohbarakeh’s leadership had embezzled the equivalent of 5.6 billion US dollars by the time their actions were discovered. The perpetrators of that financial crime were ostensibly employees of private industry, but Mohbarakeh, like many of Iran’s largest companies, is better described as quasi-state owned, with managers being appointed by senior state officials.

It should come as no surprise that regime-affiliated entities were among the beneficiaries of the embezzlement scheme. Substantial portions of the missing cash were transferred to the regime’s Revolutionary Guards, as well as the Ministry of Intelligence and Security, and at least one state media outlet. Portions also went directly to the offices of Friday “prayer leaders,” who function as local mouthpieces for the theocratic dictatorship throughout the country.

While these entities were steadily acquiring stolen wealth, the economic situation for ordinary Iranians was growing worse all the time. Ever-rising levels of poverty and unemployment have been major factors in at least nine anti-government uprisings that have taken place in Iran since the start of 2018.

In November 2019, for instance, a sharp spike in government-set gasoline prices prompted immediate, simultaneous protests in nearly 200 cities and towns, meeting a violent crackdown from regime authorities who fired into crowds and killed 1,500 people before starting a campaign of systematic torture against many of those who were detained during the unrest.

It was a testament to the severity of domestic crises at the time that unrest did not stop for long in the wake of that crackdown. And over time, the crackdown would come to stand out as a testament to the extent of the regime’s commitment to defending its own culture of corruption.

In June 2021, Ebrahim Raisi, the man who had been in charge of the judiciary two years earlier, was officially appointed as president of the regime following his endorsement by the regime’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. He rose to the presidency while countless activists and victims of the regime’s prior repression condemned him as the “butcher of Tehran.” The label derived partly from his role in the 2019 crackdown but mostly from his participation in the massacre of 30,000 political prisoners during the summer of 1988.

Raisi’s appointment to the presidency was more of an endorsement of this. The regime was and remained rattled by the escalation in popular unrest, and Khamenei no doubt expected that the “butcher” president would intimidate the public into quieting their grievances over issues like poverty, inflation, and systemic corruption spanning both government and the so-called private sector.

The strategy has been ineffective so far, and in fact, Raisi’s ascension to the presidency has only resulted in more activities “Resistance Units” to condemn him by name while also repeating well-established slogans like “death to the dictator”, which communicate popular demands for the supreme leader’s ouster and the wholesale replacement of Iran’s theocratic regime.

Ebrahim Raisi’s failure to fix Iran’s economy

The report on Mobarakeh Steel is sure to further amplify those calls for regime change, though the report only serves as further confirmation of what countless Iranians already understand. Various other incidents, such as the deadly collapse of a multi-story residential building in the city of Abadan in May, have already been highlighted by activists and protesters as symbols of the punishing effects of unmitigated corruption.

Protests over those issues have continued to face severe repression under Raisi’s nominal leadership, which has also fostered a broader culture of intimidation in the form of trends such as a skyrocketing rate of executions. In the first half of 2022, Iran, under the ruling theocracy is already firmly established as the country that implements the most annual death sentences per capita, executing more than twice as many people as during the same period in 2021. Yet this only serves to underscore both the bravery and the desperation of those who are actively pushing for comprehensive changes to the Iranian regime and society.

In the face of such defiance, the Raisi administration has been forced to lean more heavily on another tactic to supplement its violent suppression of dissent. Lately, Raisi has been joined by Khamenei in simply lying about Iran’s domestic situation in the desperate hope that that will silence some of the relevant dissent, or at least convince foreign observers that the regime is not actually in its present, historically vulnerable state.

In a speech on Monday that marked the beginning of his second year in office, Raisi made a series of preposterous claims about his administration’s own accomplishments, even contradicting reports from Iranian state media to declare that the budget deficit had declined when it had actually doubled, that the rate of inflation is falling when it actually stands at more than 50 percent, and that he had solved problems and rooted out local corruption in various communities, when in fact those communities have almost invariably met him with the now-familiar chants of “death to Raisi.”

Khamenei met with Raisi a day after the latter’s speech and echoed many of its lies. But seeing as the supreme leader has been a target of nationwide uprisings for much longer than the president, his word doesn’t have any impact other than to inflame the public hatred. In any event, recent history and emerging developments make it clear that the Iranian people will not take regime authorities seriously when they deny the prevalence of corruption. The international community should not do so either.